As a financial advisor, the question I most consistently get from my clients is “how much money do I need for retirement?” and my response is always the same – “it depends.” I know you might not necessarily want to hear that, but I can explain! There are a lot of assumptions and factors that go into this question, but the main driver is usually cash flow. So why is cash flow such a big deal? It’s because the amount you spend directly impacts what you can do now and how much you need in retirement. Most people assume they will spend less in retirement, but the truth is, many people spend the same or even more-especially in those first few years when they finally “have the time and the money” to travel and do other things as they please. There are of course expenses that may drop off in retirement, like home mortgages and student loans, but those may be offset with higher medical costs or the need for long term care.

I Hate Budgeting

The dreaded having an inflexible budget. The traditional concept of budgeting is flawed, for a variety of reasons. People hate it, it’s hard to stick to, and doesn’t take into account unexpected expenses. The goal instead should be to account for every dollar of income that comes into the pool – is it being spent or saved? This article outlines how to analyze your spending, and instead of using an unrealistic budget, set up a “cash management system”, From there, you’ll be able to run high level projections to answer the ultimate question – how much do you really need?

Where Do I Start?

The starting point is to analyze your spending. Find a spending tracker such as Mint.com, YNAB, etc. or look at your credit card year end summaries if you mainly spend from credit cards. Then, set up a spreadsheet with 4 buckets:

- Income

- Fixed Expenses

- Short term discretionary – things you buy on a weekly or monthly basis

- Intermediate and long term savings – things that you will purchase 1-5 years from now

After setting up the buckets, input all of your take home pay (after tax). If you receive other income streams, like rental property, incorporate that number in as well. It is best to back out the expenses for the rental property and just input your net income to keep things easier.

Now review your spending (I usually go back 6 months) and pull out all of your fixed expenses and input what the monthly cost is. Fixed expenses can include the following:

- Debt payments – mortgage, auto loans, student loans, etc.

- Rent

- Taxes – property tax, estimated tax payments

- Insurance – home, auto, disability, life insurance

- Utilities – gas, electric, phone, cable, etc.

- Other – child care expenses, advisor fees, etc.

Once you summarize all of your fixed expenses you should have a number for how much everything costs on a monthly basis. This is the part of your spending that doesn’t change.

Next, summarize discretionary spending. This part of the exercise is usually an eye opener since most people do not realize how much they spend. You do not need to categorize to a painful level of detail but capturing the big ticket items is helpful. If you use a spending tracker they usually break down the spending into manageable categories so you can rely on that. Some examples include:

- Food (groceries and eating out)

- Pet needs

- Shopping (put Amazon in here!)

- Auto – this would be costs outside of an auto loan payment like gas, maintenance, etc.

- Travel

Once you have your categories, go back 6 months and take an average of each category. Input that number into the spreadsheet.

After everything is in, take the total income and subtract out the fixed and discretionary spending. The number remaining “should” be your savings level. The first response a client has when I show them this number is “oh I don’t think I’m saving that much” which is almost always true. The reason why is because if cash is in our normal bank account we view it as spendable. Instead, we want to identify our post tax savings rate and be diligent about pulling it out of our normal banking system.

Now that I’ve done this exercise what do I do next?

The next step is to set up your cash buckets. Cash buckets represent current or future goals you would like to save for. The common cash buckets I see are emergency fund, travel fund, college funding and home improvements. Travel is an item that is important to many of my clients so instead of focusing on how much has someone spent on travel, I instead ask them what they would like their travel budget to be. Let’s say the travel budget for the year is $6,000. I then set the client up to put away $500/mo of their excess savings into a separate account so when they plan their next trip the funds are available.

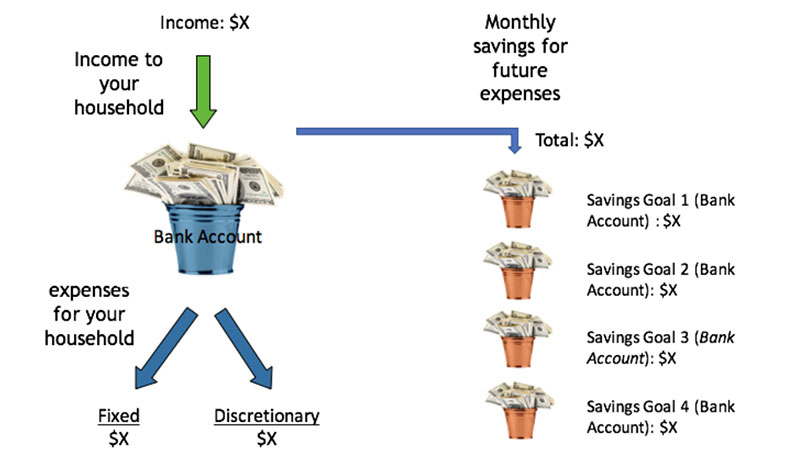

The amount of each cash bucket to fund really depends on how much excess savings is there and what the priority of the goals are. The example below outlines how to set up this system. This approach works great for people who have excess savings but just haven’t been diligent about setting up separate accounts. For clients who have a hard time saving money, there are additional steps that should be taken to remedy this.

Exhibit A

I may have a spending problem

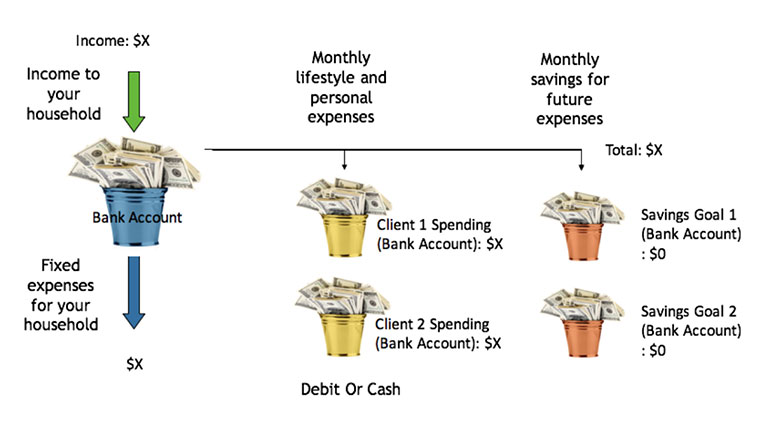

If you feel as though you spend more than you make then the second step in the process is to set yourself up with a weekly allowance. It is very common for couples to have different spending habits and it may make sense to keep separate accounts. This is not a concern and instead I focus on how much each person needs as an allowance where they each feel comfortable and are not stressed out about the other person’s spending. This is a great first step for newly married couples who are looking to explore joint finances. In this scenario, you create a joint account for all fixed expenses that will be shared. You can set this up in two ways:

- Have all income flow into the 1 account

- Decide how much each person will contribute to the fixed expenses and transfer that amount each month

Next, based on the discretionary spending average figure out that number on a weekly basis. Once that amount is determined, create either an individual or joint account for discretionary spending. (See Exhibit B) Set up an auto transfer each week of your discretionary allowance that you are permitted to spend. Once you move to this system, you must use cash or a debit card for your spending. The reason why is once you hit your weekly allowance your spending has to stop until it is replenished. This step is trial and error as you may have to adjust the allowances to find a happy medium. In any week or month where there is excess, you can put that away (in a separate savings account) for unexpected larger expenses that come up in the future. The main complaint I hear on this process is “I want to use my credit card to get points.” I completely get it, you want your points, but the problem is that credit cards tend to make people spend more than they would otherwise, so until you can get a grasp on your spending, you should use a debit card or cash. I was working with a couple who had a deficit of $6k/mo in their spending and after setting up this system they save close to $3k/mo.

Exhibit B

The great part about this system is that it forces you to think about lifestyle creep. As people’s incomes increase, their spending also increases. That is okay but only to a certain extent. When people move to this type of system, they give more thought to where their extra income and savings goes. We usually see it directed toward the long term goals bucket instead of weekly discretionary spending. People come to realize what actually brings them happiness and at the end of the day the goal is to align your money with what’s truly important.